|

|

How does a university respond to racist incidents perpetuated on its campus? Do moments of racism suggest inevitable and permanent divisions on campus or can thoughtful responses to acts of racism actually lead to a more civil community?

In 1976, February was designated as Black History Month. In February 2010, UC San Diego experienced a wave of hateful incidents targeting African American students.

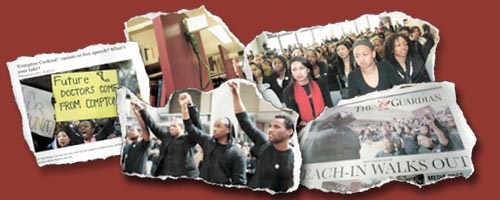

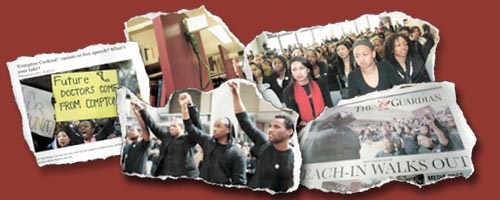

On February 15, 2010 students held an off-campus party called the “Compton Cookout.” The Facebook invitation reminded party-goers that February was Black History Month and instructed students on how to dress for the party: “For those of you who are unfamiliar with ghetto chicks-Ghetto chicks usually have gold teeth, start fights and drama, and wear cheap clothes.” Three days later, students appearing on a student-run television program used racial epithets while voicing support for the “Compton Cookout.” On February 25, a noose was found hanging in UCSD’s Giesel library and on March 2 a KKK-style hood was found draped over a statue on campus.

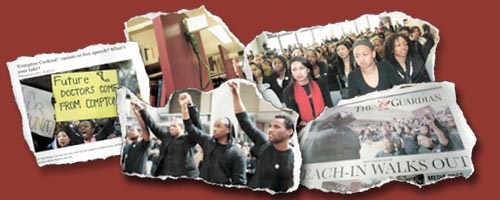

The university immediately condemned the party. UC San Diego Chancellor Marye Anne Fox quickly denounced the party and reaffirmed the campuses’ Principles of Community. On February 17, administrators held a teach-in. Twelve hundred students and faculty attended the teach-in, but halfway through, hundreds of students walked out and held their own protest calling for the university to improve the campus climate for minority students. Many students who walked out believed that a teach-in was insufficient to address the racism of the ghetto themed party and wanted the university to take “real action.”

On February 18 the UCSD administration launched a website addressing the recent hate crimes and urging the campus to “join the battle against hate.” The website lists actions taken, suggestions for what students can do, and a list of resources to educate and encourage discussion.

The incidents in February and March forced the university to confront an uncomfortable reality: African-American students make up less than 2% of the campus population. In fact, of the nine UC campuses, UC San Diego enrolled the smallest number of African American freshman in fall 2010. The UCSD Black Student Union (BSU) organized student outrage against the racist incidents in a campaign titled “real pain, real action.” The BSU submitted a list of demands to the campus administration. The BSU’s demands included increasing the number of African-Americans in all levels of the campus community from undergraduates to faculty, making the African-American studies minor stronger and more visible, and taking steps to ensure greater retention of African-American students.

Concerns about freedom of speech lay at the center of student discussions over the Compton Cookout. Students created two opposing Facebook pages. One, titled “Solidarity against racism and the Compton Cookout” expressed outrage at the party’s theme, invitation, and racist implications. The other, named “UCSD students outraged that people are outraged about the Compton Cookout” defended the party hosts’ right to freedom of speech. The group argued that political correctness has “once again, gone too far” and cited “white trash” parties as evidence that the Compton Cookout should not be targeted as racist.

The administrative and student response raises questions over what and how much the university can do in response to such incidents. Unlike the incidents at UC Davis, the events at UC San Diego were all directed towards a particular, underrepresented group on campus. This allowed the university to have a certain type of response: to increase the number of African American students and faculty, build an African American studies resource center, and have regular meetings with the Black Student Union. Would increasing the number of African American students prevent future hateful acts? Perhaps. Certainly, however, increasing black enrollment would make the university more reflective of the community and the state from which it draws the majority of its students.

These hateful acts prompted discussions over freedom of speech, racism, and civility. The events force us to question when freedom of speech and freedom of expression become hate crimes. They also demand that we examine the conditions that led to such racist outbursts. Finally, these uncivil incidents remind us that racism cannot be dismissed as a problem resolved with the Civil Rights Movement and the creation of Black History Month.

|